In the EcoSisters interview, Hiroko Oshima reflects on her transnational career as a scenographer and costume designer working between Japan and the UK, with a focus on sustainability, accessibility and healthy creative environments. Her concern emerged from witnessing the rapid disposal of sets within Japan’s fast-paced theatre system, prompting her to explore sustainable materials and translate the Theatre Green Book into Japanese. Hiroko discusses projects using recycled and sourced materials, community collaboration and material-led design processes. She emphasises the need to balance environmental responsibility, artistic integrity and accessibility, arguing that learning, shared understanding and supportive working conditions are essential for genuinely sustainable and meaningful creative practice.

Hiroko Oshima is a stage designer, researcher, and the director of Image Nation Green. After graduating from the Theatre Design course at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, she has worked on over 140 stage productions. In response to the large-scale waste generated by stage sets and costumes, she translated the Theatre Green Book, an environmental guideline for the performing arts in Japanese and she co-founded Image Nation Green, an organization that connects the performing arts and environmental action. She is currently undertaking a PhD at Lancaster University, supported by UKRI funding, where her research focuses on materials for sustainable scenography.

Contact Hiroko Oshima via:

Entre em contato com Hiroko Oshima via:

Website: www.hirokooshima.net (artist page)

Website: https://www.imagenationgreen.org/english (organization page)

*You can find the interview translated into Portuguese and Japanese below. *Você pode encontrar a entrevista traduzida para o português abaixo.

Could you please introduce yourself?

I studied theatre design in London. After I finished my BA course, I came back to Japan and started working in a scenography workshop. I worked as an administrator in the office, bridging designers and makers, such as carpenters and painters, working there for six years. Then, I received a Japanese government scholarship for emerging artists to go to Germany to intern for a year in theatre where I specialised in performance for young audiences. After this, I had a freelance career as a set and costume designer based in Tokyo before coming back to do my Masters in Theatre for Social Change in Lancaster (UK). I am currently conducting my PhD at Lancaster which is exploring sustainable materials for scenography.

Can you talk about how your interest in sustainability came about?

I’ve been working in the Japanese theatre industry for more than 20 years. In Tokyo, there are many independent productions, and most of them run for only three or four days. Because of this FAST theatre system, sets end up having extremely short lives. One day, I went to the waste disposal plant with my workshop colleagues and we threw away the scenery we had created just the week before. This was physically and visually shocking for me. All the sets were very specially designed and made with lots of handwork techniques, and I felt very sad that it had such a short moment and suddenly it was going to be garbage.

I had been thinking a lot about these concerns for a long time, but felt that I wasn’t able to do anything because it’s an industrial system that I could not change by myself. Everybody feels a little bit guilty, but there were only a few people believed that we could start to make this system change. When I discovered the Theatre Green book, I thought, “Wow, that’s great because everything is already written down”. I believe it’s important to work together so I thought that if I translate this into Japanese and share these ideas with other theatre makers in Japan, I can negotiate with many different people. In 2023, I started translating the Theatre Green book and working on sustainable scenography within my practice. So that’s how I started my artistic research, and also the sustainability movement in Japan.

Can you tell me more about your sustainable design practices?

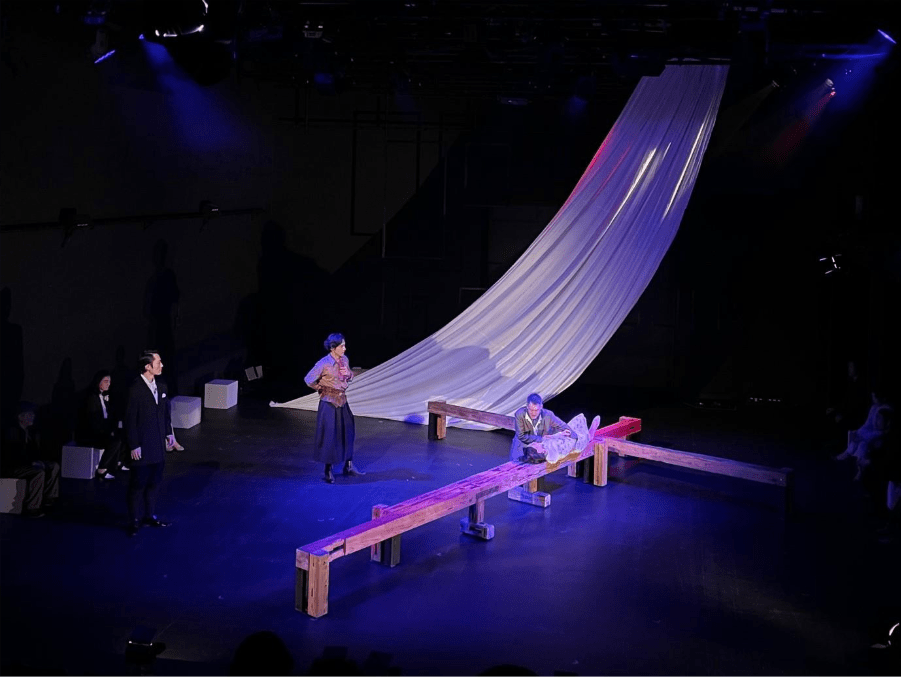

I have been working on about three or four productions using recycled materials. One was using Japanese old house timbers, turning them into scenography. Japanese traditional wooden techniques allow for simple joinery without using nails or glue. When I saw these materials, I found them quite interesting because the materials themselves have an authentic history. I could have made this the same design with traditional set-making technique, such as constructing hollow pillars using plywood and scenic finishing , but I found that if we use real materials, the effect is totally different. The old timber materials were very heavy to move for the actors but the director worked with this physicality in the performance – to produce a feeling of real heaviness. I’m not sure it was the perfect example of sustainability, but it was a good starting point for me to work is sustainable materials.

I am currently working on a theatre and forestry collaboration to make a wooden assembly tent. We went to the forest to select our tree, and the tree was cut by the woodcutter before we transported it to make timbers. We witnessed how the tree became our material. Going back to the source changes the relationship between what we design and our material choices. The project is still at the beginning, so I am not yet sure what will emerge from it.

How do you bring circularity into your design processes?

Where do materials come from and how do our materials return to the earth? That’s the process we have to really think about, and that’s what I am keen to find out. I believe that we have to explore different methods and materials, because if we completely stick with biomaterials, it might limit the design variations. I think everybody asks: how can we balance sustainability and creativity? That’s the balance we have to think about.

How do you bring eco-creativity into your design processes? (i.e., ecological approach to your artistic process)

I worked on a community-based project in Hamburg where we created an object from old T-shirts, leftover fabrics from the artist’ atelier and timber from the roadside. I just designed this shape very loosely, without knowing what it would become. I let the material features become the guide for the final design. I think that’s quite an important way of thinking, that designers let a form emerge based on a materials’ innate characteristics.

The materials, communities and artists co-created the final shape of the design. I could not imagine it by myself. It’s about everything coming together and this made the process also very freeing and enjoyable.

Do you think that being sustainable is a limitation in your aesthetics? (Why? Why not?)

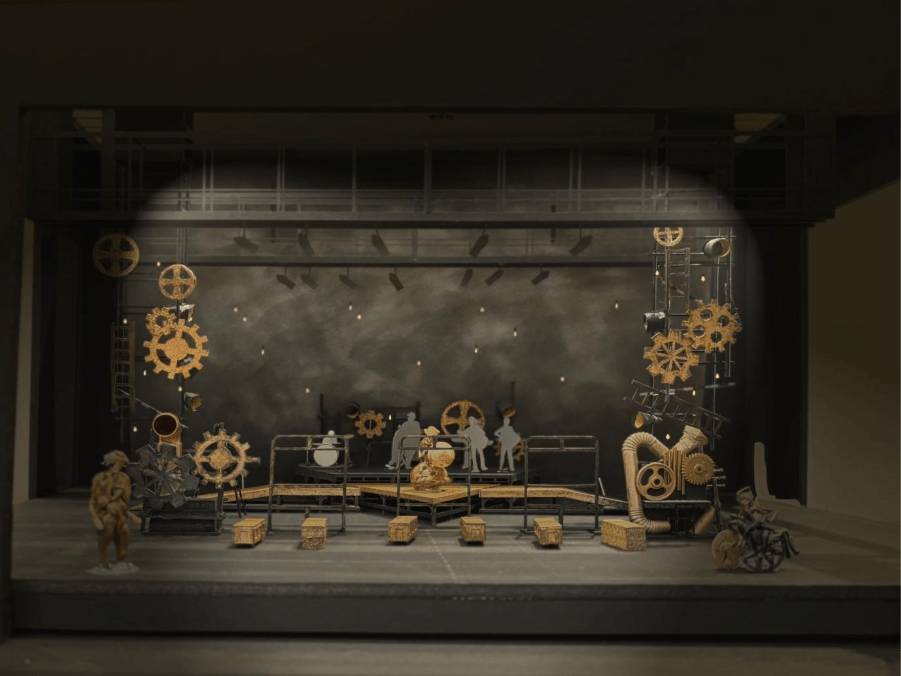

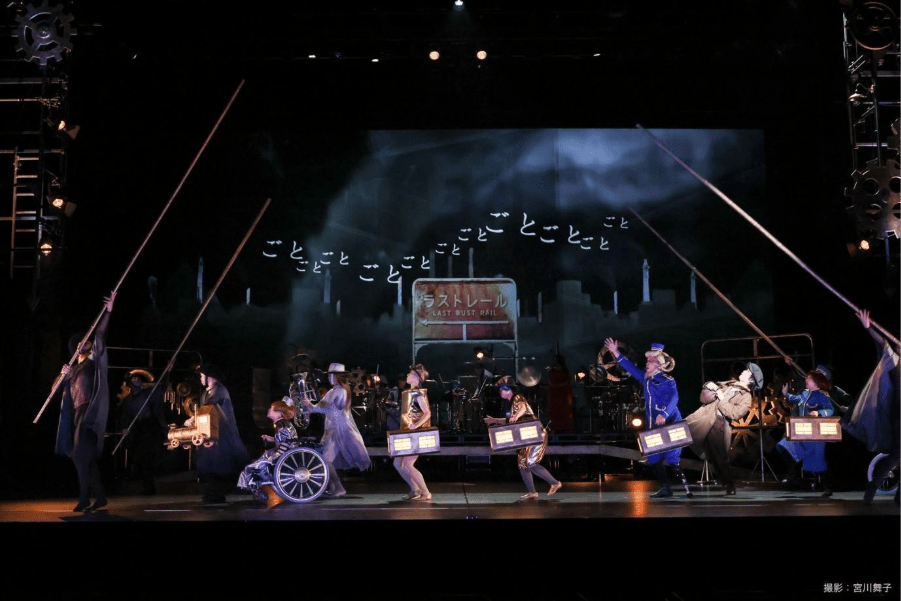

Yes and no. For example, in the production for a big theatre in Tokyo I just worked on, I didn’t focus on sustainable materials because we were exploring accessibility for the first time. We tried to integrate many layers of visual and sound information such as subtitles, sign language and audio guide from the beginning of the creation to challenge the norms of usual creative processes. I was concerned that if we focused on accessibility and sustainability together, it would be too much for the team to manage at this point in the process.

While I personally tried to incorporate sustainable practices, we ended up using gold paint (the show’s theme colour) which was very beautiful but also very unhealthy. We bought this paint, which was a golden powder, and you can mix it with the glue. On the label, it said: “Be careful not to breathe this powder. It is harmful.” I think you need to have a kind of judgment standard or your own regulation for every single project. You have balance artistic and environmental integrity and prioritize what is important to tell this message to the audience.

I think we also have to wait for technology to advance and we need less harmful materials to be invented. I think everybody should agree on certain regulations or a way of thinking about materials as a team. Each project is different. Perhaps if you can’t be perfectly environmentally friendly in the scenography, maybe you have to mitigate the impact or create positive outcomes in another way?

Have you ever worked with an organization that has an environmental policy?

No.

What would make it easier for you to do things in a greener way?

I think first of all, every theatre worker should understand the climate emergency and why we have to work in this sustainable way. Climate science is a relatively new thing. In my generation we didn’t learn about the climate emergency at school because this was before it was global concern. I think many adults are now learning about sustainability from the media, but many people don’t understand the whole picture. Learning is a very important part of understanding the fundamental issues that we must challenge. Even if we set green goals in theatres, it will be a problem if people within the organisation don’t understand why. Then sustainability just becomes a word that doesn’t make people change. Learning can be more important than having a sustainability policy. I think if it is just a policy that is pushed on to people without the ‘why’, it is easy for them to refuse it. People need to understand how important it is. Sustainability is a new idea for creation, and everybody should get excited about it. I think that’s the most important thing: to be positive, not passive.

I would like to ask if you have something else that you want to share that you think is important?

I think we shouldn’t be afraid of taking on new challenges for sustainability. The project I just worked on was about making accessibility more creative and I found this production was richer as a result. Because we had disabled artists on stage, we had a longer creation period that was also very welcoming for other staff. We had less intensive working hours and longer timeframes and everybody was very friendly in the team. It was a great environment, and I think good environments make better work. In that sense, I think sustainability also needs a longer creation period to improve our working and creative environments, and ultimately, this will lead to better outcomes all round.

*

EcoSisters: Hiroko Oshima sobre Sustentabilidade, Acessibilidade e a Importância de Promover Ambientes Criativos Saudáveis (Japão/UK)

Na entrevista EcoSisters, Hiroko Oshima compartilha sua trajetória como cenógrafa e figurinista com atuação entre o Japão e o Reino Unido, marcada por uma reflexão crítica sobre sustentabilidade, acessibilidade e ambientes criativos saudáveis. Sua inquietação surgiu ao vivenciar o descarte rápido de cenários no sistema teatral japonês, o que a levou a pesquisar materiais sustentáveis e a traduzir o Theatre Green Book para o japonês. Hiroko descreve experiências com materiais reciclados, colaborações com comunidades e processos orientados pelas características dos materiais. Para ela, sustentabilidade exige escolhas conscientes, aprendizado coletivo e equilíbrio entre ética ambiental, acessibilidade e criação artística.

Hiroko Oshima é cenógrafa, pesquisadora e diretora da Image Nation Green. Após se formar no curso de Design Teatral da Central Saint Martins, Universidade das Artes de Londres, ela trabalhou em mais de 140 produções teatrais. Em resposta ao grande volume de resíduos gerados pelos cenários e figurinos, ela traduziu para o japonês o Theatre Green Book, um guia ambiental para as artes cênicas, e cofundou a Image Nation Green, uma organização que conecta as artes cênicas e a ação ambiental. Atualmente, ela está cursando um doutorado na Universidade de Lancaster, com apoio financeiro da UKRI, onde sua pesquisa se concentra em materiais para cenografia sustentável.

Você poderia se apresentar?

Estudei design teatral em Londres. Depois que terminei meu curso de bacharelado, voltei ao Japão e comecei a trabalhar em um ateliê de cenografia. Trabalhei como administradora no escritório, fazendo a ponte entre designers e profissionais como carpinteiros e pintores, atuando lá por seis anos. Em seguida, recebi uma bolsa do governo japonês para artistas emergentes, que me permitiu ir para a Alemanha fazer um estágio de um ano em teatro, onde me especializei em performance para jovens públicos. Após isso, tive uma carreira como freelancer, trabalhando como cenógrafa e figurinista em Tóquio, antes de voltar para fazer meu mestrado em Teatro Aplicado em Lancaster (Reino Unido). Atualmente estou fazendo meu doutorado em Lancaster, explorando materiais sustentáveis para cenografia.

Você pode falar sobre como surgiu seu interesse por sustentabilidade?

Trabalho na indústria teatral japonesa há mais de 20 anos. Em Tóquio, há muitas produções independentes, e a maioria delas fica em cartaz por apenas três ou quatro dias. Devido a esse sistema teatral super-rápido, os cenários acabam tendo uma vida útil extremamente curta. Um dia, fui à usina de descarte de resíduos com meus colegas de oficina e jogamos fora o cenário que havíamos criado apenas uma semana antes. Isso foi física e visualmente chocante para mim. Todos os cenários foram especialmente projetados e feitos com muitas técnicas manuais, e fiquei muito triste por terem tido uma vida tão curta e, de repente, se tornarem lixo.

Eu vinha refletindo bastante sobre essas questões há muito tempo, mas sentia que não podia fazer nada, pois se tratava de um sistema industrial que eu não poderia mudar sozinho. Todos se sentem um pouco culpados, mas poucas pessoas acreditam que poderíamos começar a mudar esse sistema. Quando descobri o Theatre Green Book, pensei: “Uau, isso é ótimo, porque tudo já está escrito”. Acredito que é importante trabalharmos juntos, então pensei que, se traduzisse isso para o japonês e compartilhasse essas ideias com outros profissionais de teatro no Japão, poderia negociar com muitas pessoas diferentes. Em 2023, comecei a traduzir o Theatre Green Book e a trabalhar com cenografia sustentável na minha prática. Foi assim que comecei minha pesquisa artística e também o movimento de sustentabilidade no Japão.

Você pode me contar mais sobre suas práticas de design sustentável?

Tenho trabalhado em cerca de três ou quatro produções utilizando materiais reciclados. Uma delas consistiu em utilizar madeiras de casas antigas japonesas, transformando-as em cenografia. As técnicas tradicionais japonesas de trabalho em madeira permitem uma marcenaria simples, sem utilizar pregos ou cola. Quando vi estes materiais, achei-os bastante interessantes, porque os próprios materiais têm uma história autêntica. Eu poderia ter feito o mesmo projeto com técnicas tradicionais de construção de cenários, como a construção de pilares ocos usando compensado e acabamento cênico, mas descobri que, se usarmos materiais reais, o efeito é totalmente diferente. As madeiras antigas eram muito pesadas para os atores moverem, mas o diretor trabalhou com essa fisicalidade na performance – para produzir uma sensação de peso real. Não sei se foi o exemplo perfeito de sustentabilidade, mas foi um bom ponto de partida para eu trabalhar com materiais sustentáveis.

Atualmente, estou trabalhando em uma colaboração entre teatro e silvicultura para construir uma tenda de madeira. Fomos à floresta para escolher nossa árvore, que foi cortada pelo lenhador antes de ser transportada para ser transformada em madeira serrada. Testemunhamos como a árvore se tornou nosso material. Voltar à origem muda a relação entre o que projetamos e nossas escolhas de materiais. O projeto ainda está no início, então ainda não tenho certeza do que vai resultar dele.

Como você traz a circularidade para seus processos de design?

De onde vêm os materiais e como eles retornam à terra? Esse é o processo sobre o qual precisamos realmente refletir, e é isso que estou ansioso para descobrir. Acredito que precisamos explorar diferentes métodos e materiais, pois se nos limitarmos exclusivamente aos biomateriais, isso poderá restringir as variações de design. Acho que todos se perguntam: como podemos equilibrar sustentabilidade e criatividade? Esse é o equilíbrio sobre o qual precisamos refletir.

Como você incorpora a eco‑criatividade em seus processos de design? (abordagem ecológica do processo artístico)

Trabalhei num projeto comunitário em Hamburgo, onde criamos um objeto a partir de camisetas velhas, restos de tecidos do ateliê do artista e madeira recolhida à beira da estrada. Desenhei esta forma de forma muito livre, sem saber o que iria resultar. Deixei que as características do material fossem o guia para o design final. Acho que essa é uma forma de pensar bastante importante, que os designers deixem uma forma emergir com base nas características inerentes dos materiais.

Os materiais, as comunidades e os artistas co-criaram a forma final do design. Eu não poderia imaginá-la sozinha. Trata-se de tudo se encaixar, e isso tornou o processo muito libertador e agradável.

Você acha que ser sustentável é uma limitação na sua estética? (Por quê? Por que não?)

Sim e não. Por exemplo, na produção para um grande teatro em Tóquio em que acabei de trabalhar, não me concentrei em materiais sustentáveis porque estávamos explorando a acessibilidade pela primeira vez. Tentamos integrar várias camadas de informação visual e sonora, como legendas, linguagem de sinais e áudio-guia, desde o início da criação, para desafiar as normas dos processos criativos habituais. Eu estava preocupada que, se nos concentrássemos na acessibilidade e na sustentabilidade ao mesmo tempo, seria demais para a equipe gerenciar nesta fase do processo.

Embora eu pessoalmente tenha tentado incorporar práticas sustentáveis, acabamos usando tinta dourada (a cor-tema do espetáculo), que era muito bonita, mas também muito prejudicial à saúde. Compramos essa tinta, que era um pó dourado, e você pode misturá-la com cola. No rótulo, dizia: “Tenha cuidado para não respirar este pó. É prejudicial à saúde”. Acho que você precisa ter um tipo de padrão de julgamento ou sua própria regulamentação para cada projeto. É preciso equilibrar a integridade artística e ambiental e priorizar o que é importante para transmitir essa mensagem ao público.

Acho que também temos que esperar o avanço da tecnologia e precisamos que materiais menos nocivos sejam inventados. Acho que todos devem concordar com certas regras ou uma maneira de pensar sobre os materiais como uma equipe. Cada projeto é diferente. Talvez, se você não puder ser perfeitamente ecológico na cenografia, talvez tenha que mitigar o impacto ou criar resultados positivos de outra maneira?

Você já trabalhou com alguma organização que possuísse uma política ambiental formal?

Não.

O que tornaria mais fácil para você fazer as coisas de uma forma mais sustentável?

Acho que, antes de tudo, todos os profissionais do teatro devem compreender a emergência climática e por que precisamos trabalhar de forma sustentável. A ciência climática é algo relativamente novo. Na minha geração, não aprendemos sobre a emergência climática na escola, porque isso aconteceu antes de se tornar uma preocupação global. Acho que muitos adultos estão aprendendo sobre sustentabilidade pela mídia, mas muitas pessoas não compreendem o quadro completo. Aprender é uma parte muito importante para compreender as questões fundamentais que devemos enfrentar. Mesmo que estabeleçamos metas ecológicas nos teatros, será um problema se as pessoas dentro da organização não compreenderem o motivo. Então, a sustentabilidade se torna apenas uma palavra que não faz as pessoas mudarem. Aprender pode ser mais importante do que ter uma política de sustentabilidade. Acho que, se for apenas uma política imposta às pessoas sem o “porquê”, é fácil para elas recusarem. As pessoas precisam entender como isso é importante. A sustentabilidade é uma nova ideia para a criação, e todos devem se entusiasmar com ela. Acho que isso é o mais importante: ser positivo, não passivo.

Há algo mais que você gostaria de compartilhar que considere importante?

Acho que não devemos ter medo de enfrentar novos desafios em prol da sustentabilidade. O projeto em que acabei de trabalhar tinha como objetivo tornar a acessibilidade mais criativa e achei que essa produção ficou mais rica como resultado. Como tínhamos artistas com deficiência no palco, tivemos um período de criação mais longo, o que também foi muito acolhedor para os outros membros da equipe. Tivemos horários de trabalho menos intensos e prazos mais longos, e todos na equipe foram muito amigáveis. Foi um ótimo ambiente, e acho que bons ambientes geram um trabalho melhor. Nesse sentido, acho que a sustentabilidade também precisa de um período de criação mais longo para melhorar nossos ambientes de trabalho e criativos e, em última análise, isso levará a melhores resultados em todos os aspectos.

Legenda das fotos:

[1] Fotografia da peça Emilia Galotti, de Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, dirigida e traduzida por Masahiro Kiuchi, com cenografia de Hiroko Oshima (Translation Matters, 2023). Fotografia de Hiroko Oshima.

[2] Corte de madeira em uma floresta em Matsumoto (2025). Fotografia de Hiroko Oshima.

[3] Exposição ALL OWL em frente à escola (Hamburgo, 2025). Fotografia de Hiroko Oshima.

[4] Fotografia da maquete de Train Train Train, dirigida por Kaiji Moriyama, cenografia de Hiroko Oshima (Teatro Metropolitano de Tóquio, 2025). Fotografia de Maiko Miyagawa.

[5] Fotografia da peça Train Train Train, dirigida por Kaiji Moriyama, cenografia de Hiroko Oshima (Teatro Metropolitano de Tóquio, 2025). Fotografia de Maiko Miyagawa.

*

*This is an AI-translated version into Japanese.

EcoSisters:大島裕子が語るサステナビリティ、アクセシビリティ、そして健全なクリエイティブ環境を育む重要性(日本/英国)

EcoSisters のインタビューで、大島広子は、舞台美術家および衣装デザイナーとして日本とイギリスを行き来する越境的なキャリアについて振り返り、サステナビリティ、アクセシビリティ、そして健全な創造的環境に焦点を当てています。彼女の関心は、日本のスピード感のある演劇業界において舞台装置が急速に廃棄される現状を目の当たりにしたことから生まれ、持続可能な素材の探求や「Theatre Green Book」を日本語に翻訳する活動へとつながりました。広子は、リサイクル素材や調達した材料を活用したプロジェクト、コミュニティとの協働、素材主導のデザインプロセスについて語ります。彼女は、環境への責任、美的誠実さ、アクセシビリティのバランスの重要性を強調し、学び合いや理解の共有、そしてサポートのある労働環境が、本当に持続可能で意味のある創作活動には不可欠であると主張します。

1. ご自身についてご紹介ください。(舞台美術/パフォーマンス・デザイナーとしての経験年数など)

ロンドンで舞台デザインを学びました。それが私の教育の出発点です。学士課程を修了後、日本に戻り、舞台美術の工房で働き始めました。そこで事務的な業務を担当しつつ、デザイナーと大工や塗装職人などの制作者をつなぐ役割を担い、6年間勤務しました。その後、ドイツに渡り、主に児童・青少年向けの舞台を専門とする劇場でインターンとして1年間働きました。このインターンは、日本政府の若手芸術家向け奨学金を受けて行ったものです。

その後日本に帰国し、東京を拠点にフリーランスとして活動を始めました。日本の演劇制作は主に東京で行われるためです。36歳頃、今から約15年前に本格的に東京での活動を開始しました。日本の演劇界で、舞台美術家として、また衣装デザイナーとしても活動してきました。多くのプロダクションでは舞台美術と衣装は別々の役職であるため、両方を同時に担当することはあまりありません。

3年前にイギリスのランカスター大学で応用演劇を学び、修士号を取得しました。その後1年間日本に戻って東京で活動し、現在は再びランカスターに戻り、サステナブルな舞台美術の素材をテーマに博士課程の研究を行っています。

2. サステナビリティに関心を持つようになったきっかけを教えてください。(エコシナグラフィー、サステナブルな演劇実践への関心)

日本の演劇業界で20年以上働いてきましたが、キャリアの初期には大工の工房で働いていました。そこで、舞台セットを制作し、劇場に搬入して仕込み、本番後すぐにバラして、わずか10日ほどの間に最終的には埋立地へ運ばれていく、という経験をしました。東京では小規模な自主制作公演が多く、その多くが3〜4日間しか上演されません。この「ファスト」な演劇システムの中で、舞台装置は非常に短い寿命しか持たないのです。

ある日、他の工房スタッフと一緒に廃棄物処理場に行き、ちょうど1週間前に制作したばかりの舞台装置を捨てました。巨大なパネルを、すでに多くの廃棄物が集められている大きな穴に投げ入れる作業は、身体的にも視覚的にも強い衝撃がありました。どのセットも非常に丁寧に、手仕事と技術を尽くして作られていたのに、ほんの一瞬使われただけでゴミになってしまう。そのことがとても悲しく、「これは本当に良くない」と強く感じました。

こうした問題意識は長く抱いていましたが、個人では変えられない産業構造の問題であり、何もできずにいました。多くの人が多少の罪悪感を感じてはいますが、システムを変えられると信じている人は少なかったと思います。「本当に変えられないのだろうか」という疑問を長年抱きながらも、具体的な始め方が見えませんでした。

Theatre Green Bookに出会ったとき、「これは本当に素晴らしい」と思いました。すべてが明文化されていたからです。もし自分一人でこのムーブメントを始めていたら、この情報をまとめるのに10年以上かかっていたかもしれません。でも、すでにここに情報がある。これを日本語に翻訳して日本の演劇関係者と共有すれば、多くの人と交渉し、対話することができる。内容が非常に包括的で、あらゆる立場の人をカバーしているからです。

そこで2023年に、他のメンバーとともにTheatre Green Bookの翻訳を始め、同時に自分の実践としてサステナブルな舞台美術に取り組み始めました。理論的・体系的な側面と、芸術的な実践の両方を同時に進めることが重要だと考えています。こうして私のアーティスティック・リサーチと、日本でのムーブメントが始まりました。

3. サステナブルなデザインの実践について、もう少し詳しく教えてください。

これまでに、リサイクル素材を用いたプロダクションに3〜4本取り組んできました。最初の作品では、日本家屋の古材を使って舞台美術を制作しました。これは修士論文でも書いたプロジェクトです。日本の古い木造住宅で使われていた木材で、仕口のための穴が空いていたり、釘や接着剤を使わずに組み合わさるよう、突起が残っていたりします。日本の伝統的な木工技術ですね。

これらの素材を見たとき、素材そのものが本物の歴史を持っている点にとても魅力を感じました。デザイン自体は非常にシンプルでしたが、劇場空間の中で空間を変化させる構造体として使いました。合板で中空の柱を作り、エイジング塗装を施すという従来の舞台美術技法でも同じ形は作れたと思いますが、本物の素材を使うことで、効果はまったく異なるものになりました。

俳優にとっては非常に重く、動かすのが大変でしたが、演出家はその困難さを演技に取り入れました。素材の重さを身体で感じる、その物理的な感覚が舞台に残ったと思います。完璧な例だったかは分かりませんが、サステナブルな素材に取り組むための良い出発点でした。

現在は、ある劇団と林業会社と協働し、木製の組立式テントを制作しています。三者で森に入り、使う木を選び、伐採し、製材される過程を一緒に見ました。素材がどのように生まれるのかを目撃し、その原材料から舞台美術を作っています。このプロセスは、通常の舞台美術制作では省略されがちです。木という原材料から始めたら、デザインと素材の関係性が変わるのではないか。これが次のプロジェクトです。まだ始まったばかりで具体的な完成像はありませんが、とても重要な問いだと思っています。

4. デザインプロセスにどのように循環性(サーキュラリティ)を取り入れていますか。

素材がどこから来て、最終的にどのように大地へ戻っていくのか。これが次に考えるべき課題です。舞台美術が自然に還るプロセスを、本気で考えなければなりません。

例えば、完全にバイオマテリアルだけにこだわると、デザインのバリエーションが制限される可能性があります。誰もが「サステナビリティと創造性をどう両立させるか?」という問いを抱いていると思います。そのバランスを丁寧に考えることが必要だと感じています。

5. デザインプロセスにおいて、どのようにエコ・クリエイティビティ(生態学的な創造性)を取り入れていますか。

ハンブルクで行った別のプロジェクトでは、高さ約3メートル、幅約2メートルのオブジェを制作しました。現地のレジデンスセンターに所属するインディペンデント・アーティスト、地元の学校、そしてさまざまな障害を持つアーティストとの協働でした。

素材には、古いTシャツやアトリエに残っていた布の端切れを使い、骨組みにはハンブルクの道端で伐採された植物(竹のような素材)を使用しました。形は非常にラフにしかデザインせず、完成形を明確には想像していませんでした。素材が集まる過程そのものが、自然とデザインの方向性を決めていったのです。

デザイナーとして、素材の特性に形を委ねる。素材の特徴から最終形が立ち上がってくる。この考え方はとても重要だと思います。

このプロジェクトでは、素材、アーティスト、学生、すべてが一緒になって形を共創しました。一人では想像できないものです。すべてが集まり、この形になった。ある意味で、とても自由でした。すべての要素に自分一人が責任を負うのではなく、みんなのアイデアが集まる。そのプロセスをとても楽しみました。

また、スタンプ制作のワークショップを行い、学生たちは「私たちは埋もれたくない」「みんな一緒」「No hate」など、社会に向けたメッセージを考えました。多様な声が、一つのオブジェの中に集約されました。

6. サステナブルであることは、美的表現の制限になりますか。(なぜ/なぜならないのか)

はい、そしていいえ、です。例えば、直近で関わった大規模プロダクションでは、サステナブル素材をテーマにはしませんでした。東京都が関わる大劇場での公演で、「クリエイティブ・アクセシビリティ」という新しい試みに初めて挑戦したからです。字幕、手話、音声ガイドなど、複数の視覚・聴覚情報を創作の最初から統合するという挑戦でした。

アクセシビリティとサステナビリティを同時に扱うのは負荷が大きすぎると判断しました。ただし個人的には、劇場にあるものをできる限り活用し、新作と既存のユニット舞台やパイプなどを組み合わせました。

全体のテーマカラーはゴールドで、非常に美しい塗料でしたが、健康には非常に有害なものでした。ラベルには「吸い込まないよう注意。有害」と書かれていました。そこで常に選択が迫られます。プロジェクトごとに、自分なりの判断基準や優先順位が必要です。

観客に何を伝えることが最も重要なのか、環境への影響をどうバランスさせ、どう軽減するのか。技術の進歩を待つ必要もあります。より害の少ない素材が開発されることを期待しています。

チーム全体で今回の優先事項に合意できれば、その中で最善を尽くすことができます。完璧に環境負荷ゼロにできない場合は、別の形で影響を相殺する工夫も必要かもしれません。例えば、広報に力を入れたり、ワークショップを行ったりするなど、オフセット的な発想です。

7. 環境方針を持つ組織と仕事をしたことはありますか。

いいえ、ありません。

8. より環境に配慮した取り組みを行いやすくするために、何が必要だと思いますか。

まず第一に、すべての演劇関係者が気候危機を理解し、なぜサステナブルな働き方が必要なのかを知ることだと思います。気候科学は比較的新しい分野で、私の世代は学校で学んでいませんでした。多くの大人はメディアから断片的な情報を得ていますが、全体像を理解していない人も多いと感じます。

学ぶことが何よりも重要です。マネージャーが環境目標や方針を掲げても、なぜそれが必要なのかを理解していなければ、ただの言葉で終わってしまいます。

その通りです。理解のレベルが揃って初めて変化が起こります。方針を上から押し付けられるだけでは、人は拒否します。サステナビリティは新しい創作のアイデアであり、ポジティブに、ワクワクしながら取り組むべきだと思います。

9. ほかに共有しておきたい重要なことはありますか。

直近のプロジェクトはアクセシビリティがテーマでしたが、「クリエイティブ・アクセシビリティ」を目指しました。通常、字幕や手話は後付けされがちですが、今回は創作の最初から組み込みました。その結果、作品はより豊かなものになりました。

サステナビリティも同じように取り組めると思います。適切な方法で取り組めば、創作に良い影響を与えます。恐れずに新しい挑戦をすべきです。

障害のあるアーティストが参加したことで、制作期間を長く取り、労働時間も緩やかになり、チーム全体にとって良い環境が生まれました。良い環境は、より良い作品につながります。

サステナビリティにも、考え、対話するための時間が必要です。それが制作環境を改善し、結果としてより良い作品につながると信じています。